Convict. Inmate. Thief. Prisoner 24601.

Maybe you recognize this number from the Broadway musical-turned-film Les Misérables, based on Victor Hugo’s book about a former prisoner, Jean Valjean, who experiences redemption.

Valjean served time for stealing bread during an economic recession in 18th century France to help feed his sister’s children, and throughout the story he is chased by his past and his identity as prisoner 24601.

There are over 10 million people around the world who currently hold the label “prisoner” or “inmate”.

In the United States, according to the Sentencing Project, 70 to 100 million people have some type of criminal record and have been stigmatized and legally discriminated against in housing, employment, education and public benefits.

As Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative and author of Just Mercy, wrote, “Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.” But many people continue to carry the label of their worst mistake long after their release.

Like Valjean was forced to carry a yellow passport identifying him as a former convict and branding him as an outcast, men and women trying to reenter society in the United States find themselves checking boxes on applications for housing, employment, education and public benefits that allow them to be legally discriminated against.

This box carries a stigma that allows no room for nuance or redemption.

These labels, like most other labels, over-generalizations and stereotypes, can be harmful. And the pain of being put in a box and defined by a label is something we all experience. This past year, we have seen these labels deteriorate relationships through political commentaries by friends and family online.

When we allow ourselves to get caught up in labels, and fail to acknowledge the uniqueness of each person, it is far easier to categorize them as “other” and dehumanize them.

There are over 10 million people around the world who hold the label “prisoner.” They have been branded by this word. But when Crossroads invites them to tell us who they are in the Who are You? Bible study course, “prisoner” rarely makes the list.

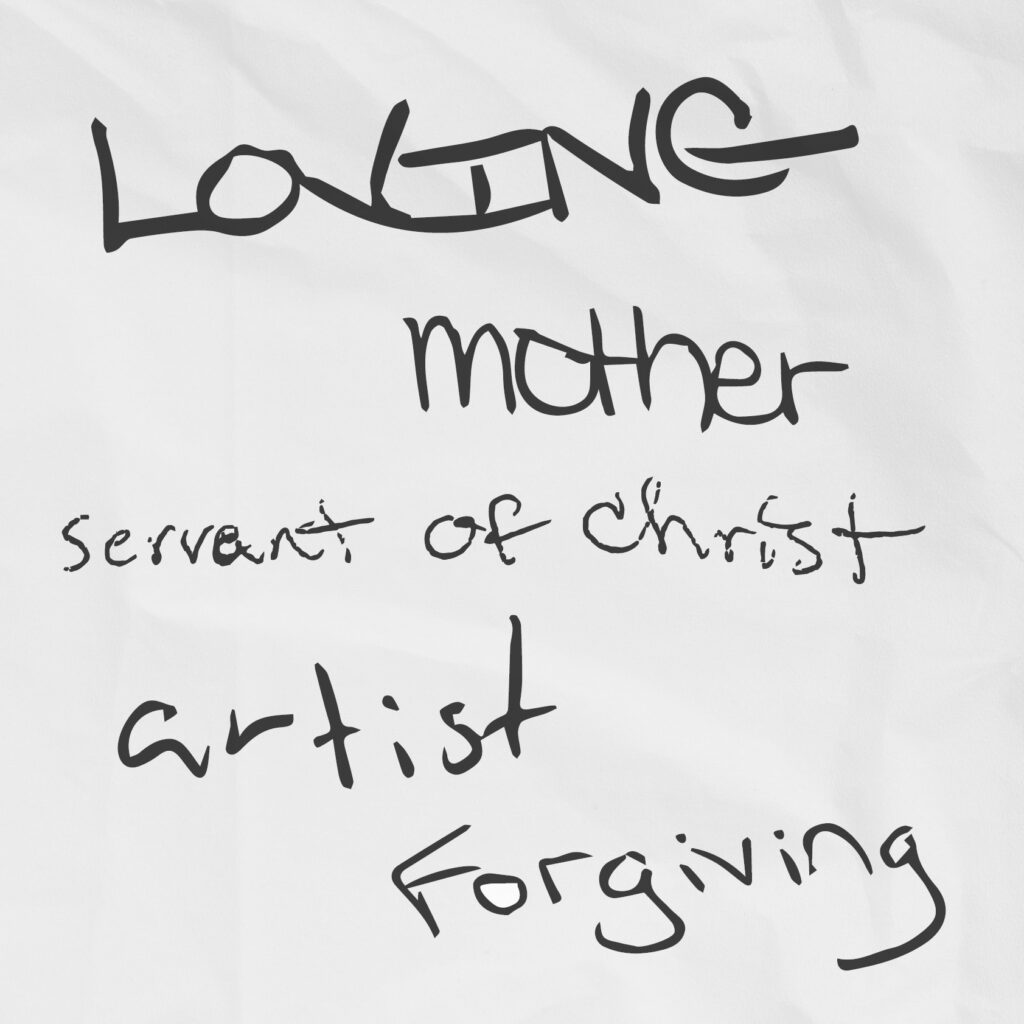

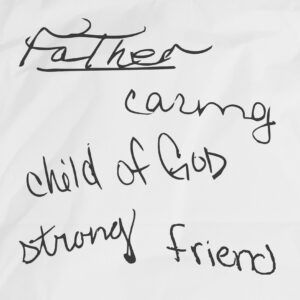

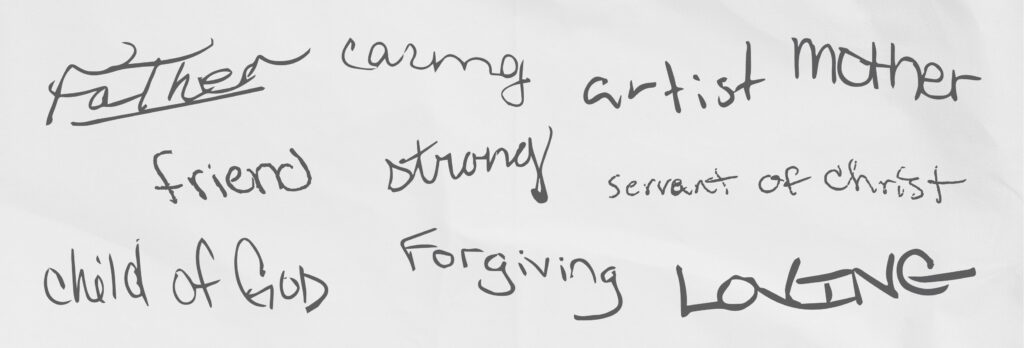

The labels they choose, when answering the question “Who are you?”, are often: Mother. Father. Daughter. Son. Sister. Brother. Niece. Nephew. Friend. Wife. Husband. Widow. Uncle. Aunt. Child of God.

They describe themselves not by the words you would associate with the harsh rhetoric surrounding crime, but with the words: Caring. Determined. Loving. Giving. Nice. Strong. Loved. Lonely. Believer. Kind. Artist. Beautiful. Forgiven.

When we step into relationship, when we ask people who they are, we can remove the labels and see them as God sees them—dearly beloved children.

“So in Christ Jesus you are all children of God through faith.” -Galatians 3:26

“To love another person is to see the face of God.” – Victor Hugo

Convict. Inmate. Thief. Prisoner 24601.

Maybe you recognize this number from the Broadway musical-turned-film Les Misérables, based on Victor Hugo’s book about a former prisoner, Jean Valjean, who experiences redemption.

Valjean served time for stealing bread during an economic recession in 18th century France to help feed his sister’s children, and throughout the story he is chased by his past and his identity as prisoner 24601.

There are over 10 million people around the world who currently hold the label “prisoner” or “inmate”.

In the United States, according to the Sentencing Project, 70 to 100 million people have some type of criminal record and have been stigmatized and legally discriminated against in housing, employment, education and public benefits.

As Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative and author of Just Mercy, wrote, “Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.” But many people continue to carry the label of their worst mistake long after their release.

Like Valjean was forced to carry a yellow passport identifying him as a former convict and branding him as an outcast, men and women trying to reenter society in the United States find themselves checking boxes on applications for housing, employment, education and public benefits that allow them to be legally discriminated against.

This box carries a stigma that allows no room for nuance or redemption.

These labels, like most other labels, over-generalizations and stereotypes, can be harmful. And the pain of being put in a box and defined by a label is something we all experience. This past year, we have seen these labels deteriorate relationships through political commentaries by friends and family online.

When we allow ourselves to get caught up in labels, and fail to acknowledge the uniqueness of each person, it is far easier to categorize them as “other” and dehumanize them.

There are over 10 million people around the world who hold the label “prisoner.” They have been branded by this word. But when Crossroads invites them to tell us who they are in the Who are You? Bible study course, “prisoner” rarely makes the list.

The labels they choose, when answering the question “Who are you?”, are often: Mother. Father. Daughter. Son. Sister. Brother. Niece. Nephew. Friend. Wife. Husband. Widow. Uncle. Aunt. Child of God.

They describe themselves not by the words you would associate with the harsh rhetoric surrounding crime, but with the words: Caring. Determined. Loving. Giving. Nice. Strong. Loved. Lonely. Believer. Kind. Artist. Beautiful. Forgiven.

When we step into relationship, when we ask people who they are, we can remove the labels and see them as God sees them—dearly beloved children.

“So in Christ Jesus you are all children of God through faith.” -Galatians 3:26

“To love another person is to see the face of God.” – Victor Hugo